An old boss of mine once told me that journalism is storytelling with a purpose. I didn’t know it at the time, but he nicked the phrase from a well-respected book called The Elements of Journalism.

This person believed good quality journalism was long-form text, story-telling narratives, verbose authors all printed in a broadsheet newspapers. Quite right…in the 1950s.

The role of the humble story-teller with purpose has changed immensely in the last decade, driven by the incredibly rapid, social-media driven shift in how audiences consume content.

Legacy media ideals are risking the future of digital journalism

BuzzFeed CEO Jonah Peretti noted in his end of year memo to staff that ‘legacy media’ channels like mainstream newspapers have been ‘much to slow to shift to digital’. This has created a vacuum in advertising spend where the biggest budgets are still too often tied up funding the 1950s view of quality journalism, rather than evolving that view for the digital age.

This scenario has created two key problems for digital journalism:

It is beset with quality issues, because the vacuum is being filled with low-quality content

The funding for good quality, bespoke digital journalism isn’t as plentiful as people think

Peretti’s own organisation is bearing the scars of this trend, laying off 15% of its total staff in January. And while the news media industry has become accustomed to redundancies in recent times, seeing the axe fall at a company which practically invented web2.0 journalism is a signal that things need to change.

Social media’s role in consuming digital journalism

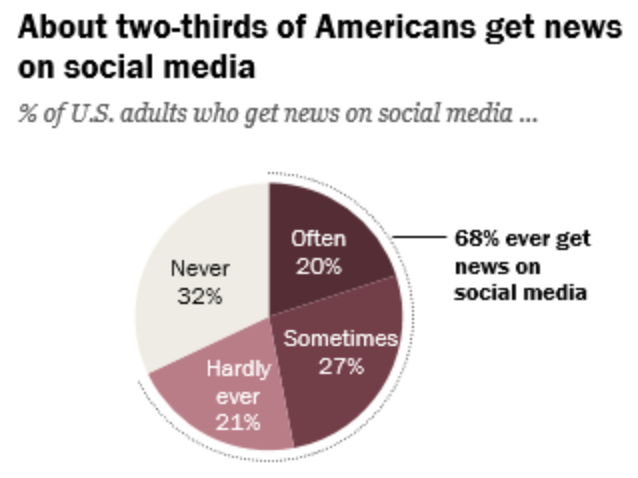

It’s undeniable that social channels now play a huge part in how we consume digital media.

Around 68% of adults in the US get at least some of their news from social media platforms, and the majority of those cite Facebook as the primary source.

Unique content is vital to Facebook’s advertising duopoly.

Digital media in part drives engagement with the big two’s platforms, so it is no surprise that they have invested in ventures to sustain news content, like their funding of local news services in the US.

But digital journalism can’t rely on the good graces of the online ad monoliths to survive. It needs to find a way to sustain itself.

Commercialising content will require journalistic adaptation

Programmatic display ads appeared to herald a long-term source of funding for digital media, but with spend on open display networks (traditionally the most important revenue source for news media sites) set to decline it’s clear digital journalism can’t rely on the ‘show-it-and-bank-it’ mentality of the past.

Commerce content could be the answer, where digital media publishers produce pieces of content (or sections of content within larger articles) that are specifically for monetisation purposes.

To make this a reality of course journalists need to adapt.

Content needs to be written more with commerce in mind. That’s not to say journalistic integrity needs to be betrayed. But journalists need to create content where opportunities for embedded, monetised links that generate revenue from the written content that is ultimately the most important asset of a digital media outlet is vital to the future of online journalism.

Subtle, embedded commerce content can enhance the quality of digital journalism, and this presents an opportunity for journalists to adapt in their roles, considering what point in the purchase cycle their reader may be in, and how their authorship can not only educate but influence in more ways than one.

The role of the content creator

The traditional gap between journalists that create the content and the advertising teams that sell eyeballs is gone. In its place, the content creator now needs to be part traditional journalist and part commercial owner, thinking not only about how their content engages an audience, but how it generates revenue.

This is the way digital journalism will safeguard quality while also ensuring that the vast majority of digital media continues to be freely available.

The paywall option

The other option is of course to eschew the internet’s traditional principle of free-to-air content and return to the ‘newsstand’ principle where consumers pay for their digital content. Pay-walls are of course working for some major news outlets.

The New York Times recently reported 18% growth in revenues from subscription based content.

While a much softer approach, both The Guardian and Wikipedia frequently ask for donations to keep their content free for the masses.

The problem with paid for online content is it will only work for the very largest digital media outlets. While a consumer might pay to access their most-read media outlet, they are unlikely to pay to access their ten most-read media outlets.

So, everything the journalistic community hate about Facebook and Google’s dominance of content delivery may effectively be recreated amongst digital media outlets with pay-wall guarded digital news monopolised by the biggest companies to the determinant of choice.

How does the story end?

This brings us back to the definition of journalism.

Storytelling with a purpose, is now storytelling with a purpose and a commercial upside. And while my old boss may have damned this notion as journalistic heresy, the content creators of today can not afford to do the same.